|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

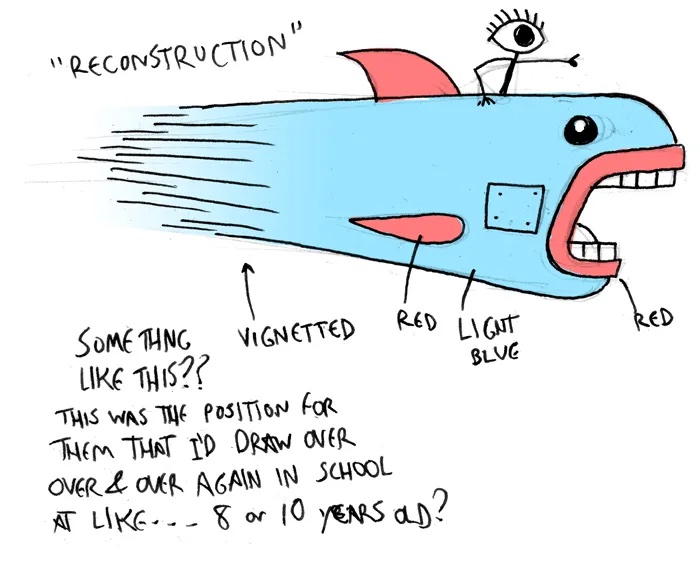

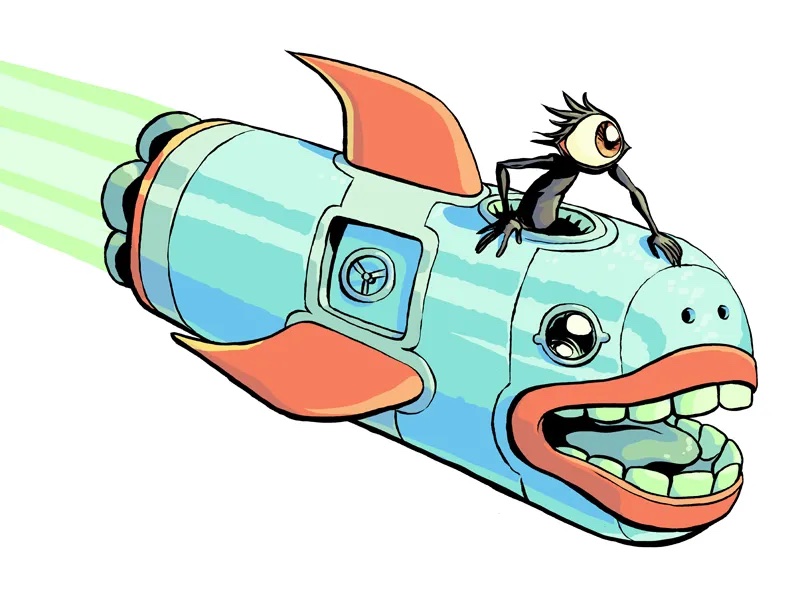

Making, SeeingThis is from January 2018.  In elementary school when I was 8 or 9 I remember drawing these two characters that had seemed to emerge as fully-formed visual objects in my head — a simple figure with an eye for a head, and a sort of fish-clown-rocketship. They were called Eyeball and Bigmouth. I drew them constantly in the same pose I’d originally come up with, I came up with some affiliated characters I don’t remember… I drew probably under 10 pages of proto-comics about them with a couple of friends I think? I only dimly remember any of this! But I was obsessed with these characters; more importantly I was obsessed with the idea that some imaginal thing like this could just be granted to me apparently out of thin air and I could make it clearer and clearer by drawing it.  I’m thinking about this lately because I’m more and more trying to work through my relationship to the creative aspect that you might call the “visionary” or the “surreal:” the idea that creative objects can emerge as if spontaneously, and that a large part of creative work can be thought of as unlearning the rationalizing, intellectualizing layers that inhibit access to “the subconscious,” or call it what you like. That creative work, and maybe more than that, is definable as a tension between the critical and the automatic/visionary (for the purposes of this essay I’ll call it the surreal because nobody’s really talked about it more clearly than the Surrealists, I think). My recent book in the Ley Lines series is a very loose attempt to explore these ideas. Hard to talk about this stuff without seeming flaky or mystical, though, isn’t it. — Rice Boy was the first major comic book that I made; I started it in 2006 when I was 18 — so, closer to the Eyeball & Bigmouth drawings than to now, at this point; that’s a disorienting thought. After making a bunch of less personally involved, more action-oriented comics for a couple of years at entervoid.com and elsewhere, Rice Boy felt revelatory to me. Like I was figuring out the sort of work I could make that was actually mine, and that didn’t feel disingenuous. In retrospect I can look at it as a way of developing the same sort of interest in the surreal: very early on, my approach to making that book was effectively to work hypnagogic and automatic imagery into as rigorously consistent a fantastic setting as I could manage. The other books I’ve made in the same setting as Rice Boy are, maybe necessarily, less visually digressive and weird. I think the literalistic conventions of the fantasy genre I’ve been digging into, the needs of interstory continuity (or even the suggestion of it), and the direction I’ve been taking Vattu towards naturalistic presentation of (for-me) plot-heavy content have ended up being destructive to the surreal aspect of what I started out trying to do. I think it’s arbitrary whether or not I think of this as a Problem, and I’m happy with how the work I’m involved in now is going. But anyway I’m thinking a lot lately about trajectories and creative habits, and I’m thinking about what approach I’d like to take towards the surreal and towards the literalistic-fantastic in future work. Rice Boy feels like a kind of fulcrum around which I can think about this stuff — this book I made so long ago a different person might as well have made it. - I think it can be useful to think of creative work as occupying the tension between the surreal/visionary/”inspired” and the critical/conscious/intellectual. This is simplistic but it’s something I can map onto my own work to get a sense of what I’m doing with it, at least. I think it’s clear that the overriding cultural pressure on art and artists is in the direction of intellectual engagement in the extreme — to boil every creative concern down to a question of technique, to eliminate the mysterious, or any aspect of a work not verbally explicable by its creator. This is the way, increasingly, we’re pressured to interact with art even as its audience: as diviners of specific conscious intentions, as connectors of little detailed dots, as scriptural literalists. Even our engagement with subtextual thematic and sociopolitical content more and more becomes a question of assembling puzzles or decoding flat cyphers. This isn’t necessarily to say that the more mysterious aspects are preferable or more noble, just that in this frame the lacks in how art is thought about become conspicuous. The Surrealists talk about this of course, but JRR Tolkien does too, or about something parallel to it, in the essay “On Fairy-Stories.” He makes something like an analogy between the surreal/inspired space I’ve been talking about and the folkloric idea of Fairy-land, and sees as central to his project the use of intellectualized scaffolding to build as direct a connection to that “place” as he can. — Looking at Bigmouth, the rocket-fish, I see that he’s clearly a reconfiguration of the Glove from the Yellow Submarine, of which I had a plastic toy of at the time, I think. And in the visual texture of Rice Boy, I can see little riffs I didn’t know I was making on the looks of old Betty Boop cartoons, Transformers: the Movie (1986), some Bakshi movies… It seems pretty straightforward in this way to see emergent images as reconfigurations at random of existing visual input. I think when someone’s doing automatic or otherwise Surreal work, there’s a clearer conduit to the raw imaginal material in the brain, and I understand that material to be totally chaotic and reckless combinations of the perceived visual world. As visual culture has become more erratic and one’s involvement in it gets more deep, the imagery gets weirder and denser. — I think there’s a window into the perceptual process in our experience of visionary/hypnagogic/hallucinatory images. We, maybe necessarily, think of perception as a passive process: we are neutral, objective camera-creatures, the world passes before our eyes and we take it in just the way it Looks. This is an understanding made possible culturally, or at least powerfully reified, by the existence of optical technology on the continuum of the camera. But the process of perception seems to be more creative and active than that. The apparent complexity of the visual world is so enormous that it’s inconceivable that your brain could record all of it objectively, high-resolution-camera-style. Your brain must be constantly working to effectively build it around you: making assumptions, overcorrections, and tiny creative acts to allow for something we can interact with as if it were a consistent visual space. And all the while it must be checking its work against feedback from the actual optical apparatus. This must be a process undertaken constantly on distinct levels: between granular visual interpretation and incorporation into a socially-comprehensible seen world. We could maybe draw a distinction between the “visual (human perceptual lifeworld)” and “optical (camera/objectivity myth).” Neurologist Sue Blackmore talks a lot about this sort of thing in as accessible a way as I’ve found. This lecture is also good. Think that the entirety of consistent visual space that you perceive is a created thing inside your head. It’s created using the raw material of optical input and socially-arrived-upon conclusions about what the world Looks like, but that doesn’t minimize the enormity of the creative act very much, to me. Hypnagogia, hallucination, and other potential taps into surreal space provide a window into this process: what does the visual apparatus do when closed off from having to interpret optical input? I think everyone has these images, effectively a constant stream of them — the dawdles and the excrement of the visual process. But it can be tricky to see them; it’s a layer of perception that’s necessarily sublimated. Doodling or automatic drawing has always been the most direct tap for me — a technology to correct for the dreamlike slipperiness and unaccountability of subliminal images. Maybe the point at which I differ from the Surrealist framing is that I don’t see the space from which these images seem spontaneously to emerge as a place of any sort of transcendent truth or beauty. Their value to me is exactly in their meaning-agnosticism, their chaos and heterogeneity. But maybe if I had any serious metaphysical beliefs I’d rationalize them some other way. Part of my interest in this is as a way of deconstructing how I interact with the world, and the various myths of objectivity we seem to be preoccupied with. What conclusions can we draw from an understanding that we don’t perceive the visual world objectively? What conclusions can we draw from the occasional glimpses we get at the raw and noisy subliminal content of our minds? |